More Than Just A Love Story

By Phil Brigandi, Pageant Historian

The Ramona Outdoor Play is much more than just a love story. Woven into the romance of Ramona and Alessandro is a glimpse of the tragic history of Southern California’s native people. It is a love story with a moral, a message that is as important today as it was when the story of Ramona was written more than a century ago.

“Ramona” began as a novel, published in 1884 by Helen Hunt Jackson, one of America’s most popular women writers of her day. Though never one to get involved in social causes, in the year 1879 Jackson had suddenly emerged as one of America’s leading advocates of Indian rights. She called for changes in the government’s Indian policies and documented their past crimes in her 1881 book, “A Century of Dishonor”.

The outlook seemed bleak. Jackson described in vivid detail the broken treaties, brutal murders and evictions the Indians had endured. Forced onto reservations, disease and death soon took their toll. America’s Indians were heading towards extinction. “I sometimes wonder that the Lord does not rain fire and brimstone on this land,” Jackson wrote to a friend, “to punish us for cruelty to these unfortunate Indians.”

Jackson had hoped her book would lift the American people to the same sort of outrage she felt over the treatment of the Indians. When it did not, she decided to try to write a novel that would “move people’s hearts. People will read a novel when they will not read serious books,” she wrote. She called her novel “Ramona.” The story begins on a Mexican rancho in the California of the 1850s, but the setting and the characters are just the “sugar-coating of the pill”, as Jackson put it.

There was no real Ramona, no real rancho of the Senora Moreno. All of that was just part of Jackson’s plan to lure readers into the story. “I thought if I could write a story so interesting that people could not put it down,” she explained, “and weave into that story the true history of some of the Indians’ sufferings, I might thus, as Paul says, “(perhaps) convince some.”

Jackson realized that most Americans were not sympathetic toward Indians, thus she tried to disguise her reform message in a love story. She does not preach, she does not moralize. She makes the story her message and lets her readers draw their own meaning.

While Ramona and Alessandro are only fictional characters, the “Indian history” in “Ramona” (as Jackson put it) is all based on actual events that took place in Southern California in the 1870s and ‘80s.

Jackson wove these real events into her novel so no one could accuse her of exaggeration; they were a part of history and the facts were there in court records, newspaper articles and government reports for all to see.

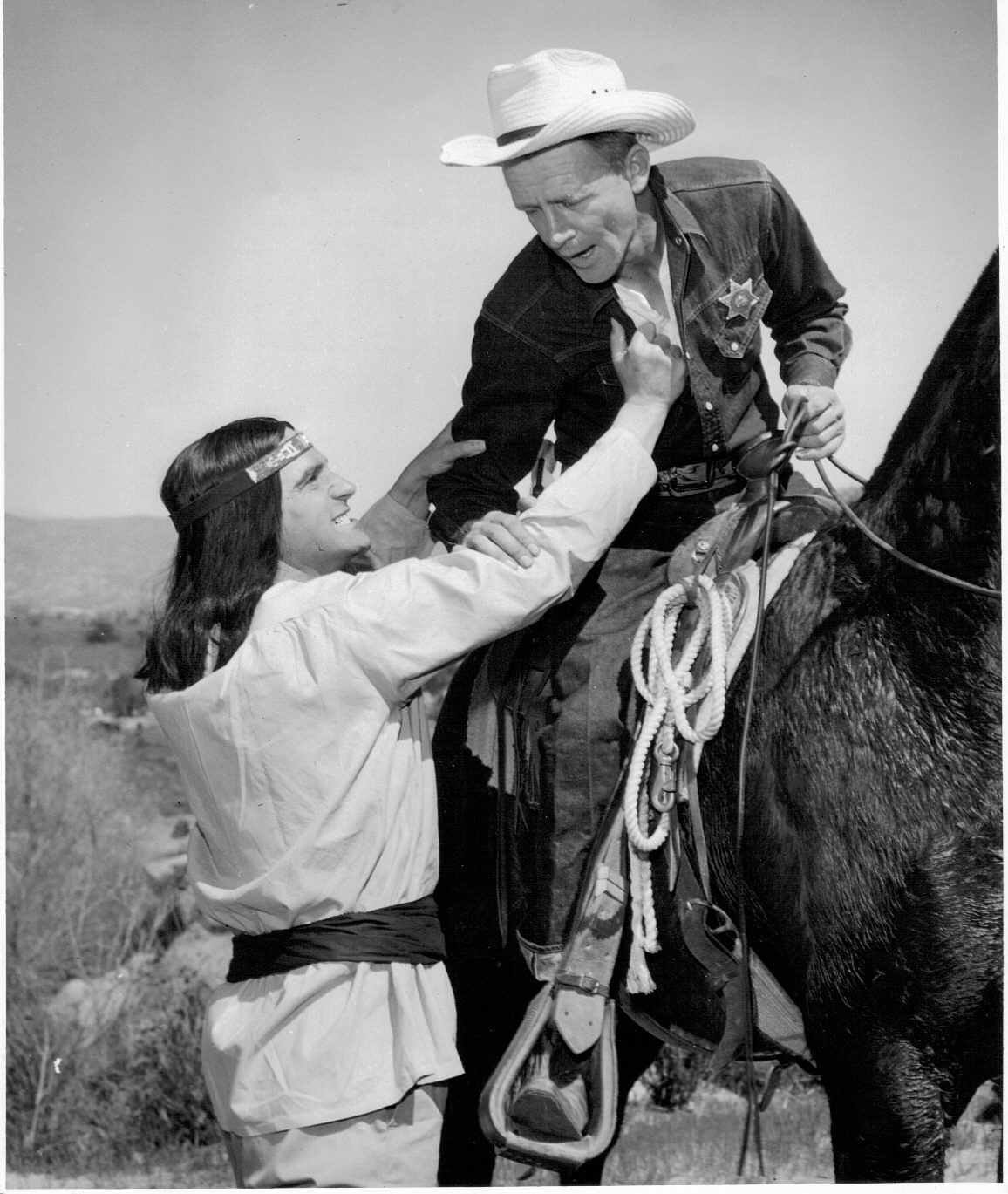

The destruction of Alessandro’s village at Temecula is based on a real event. In 1875 the Sheriff of San Diego County rode into the Luiseno village at Temecula and served an eviction notice. The Sheriff also confiscated the Indians’ livestock to pay court costs for the lawsuit that forced them from their homes. It took four days to strip the village, Jackson wrote in 1883. The ruins of some of the houses are still standing as is their neatly walled graveyard, filled with graves, a cross at the head of each mound. After the eviction, many of the Indians settled nearby at Pechanga, “a spot so barren and dry no white man had thought it worthwhile to take up the land,” Jackson noted. Eventually, Pechanga was set aside for them as a reservation. Through hard work, the Indians managed to make a living off the rugged rolling hills.

When Hayton offers Alessandro a little money to pay for his home and crops on the land Hayton had already filed on it with the government, he is playing out a real incident that occurred at the Los Coyotes village near Warner Hot Springs in San Diego County in 1883. A white man named Bill Fain moved into the village and offered the Indians a token payment. “They refused to sell,” Jackson wrote in an official report to the government, “upon which he told them that he had filed on the land, should stay in any event, and proceeded to cut down trees and build a corral…in the heart of this Indian village (of 84 people), which he was avowedly making ready to steal, as if he had been in an empty wilderness.”

It was not until 1889 that Fain and the other white settlers on the mountain were finally evicted from the Indian villages there and the Los Coyotes Indian Reservation was created. When Ysidro loses his lands, even though he holds a deed signed by the former Mexican Governor of California, Jackson is portraying the fate of the Indian village at San Pasqual in the 1870s.

The village there had been recognized as an organized pueblo by the Mexican government, but despite the United States’ promise to respect all existing property rights when California passed from Mexico to the United States at the end of the Mexican War, the American government ruled the entire valley was public domain, which could be filed on by homesteaders.

After visiting the area in 1883, Jackson wrote: “The Indians are all gone; some to other villages, some living nearby in canyons and nooks in the hills, from which, on the occasional visits of the priest, they gather and hold services in the half-ruined adobe chapel built by them in the days of their prosperity.”

Even Alessandro’s death, the climax of the story, is based on the 1883 murder of Juan Diego, a Cahuilla Indian, by Sam Temple, a San Jacinto wagon driver. Temple accused Diego of stealing one of his horses, rode to Diego’s home in a little valley in the mountain above Hemet, and shot him dead in his own doorway while Diego’s wife watched in horror.

Temple returned, pleads self-defense to the local Justice of the Peace, and is let off without even a trial. “It is easy to see that killing of Indians is not a very dangerous thing to do in San Diego County,” Jackson wrote shortly after the murder. Tragedies such as these were all too common in Southern California in the 19th century.

Many who read “Ramona” or witness the Ramona Outdoor Play still see it only as a love story; but it is much, much more. Jackson’s message still haunts us. She asks us to look at the wrongs of the past so that we might try to change the future. In the Ramona Pageant perhaps Father Gaspara says it best; “And as for you…Hear now the words of truth. You stand on law, on might and on the power of wealth. On these things justice can never grow. Beware the time when your great people rule the world only by wealth. The Indian now is driven out – so Christ will be! Take the Indians’ land yet they hear the sacred word: ’What shall it profit a man if he gains the whole world and lose his own soul?’”

As you watch the Ramona Outdoor Play try to see it the way Mrs. Jackson would have wanted you to see it.

Her message is there, for all who will listen.